How the media's double standard is failing refugees

Published: 12 September 2025

Jess Casot tests whether biases extended to representation in the media, comparing how Ukrainian refugees have been visualised and reported, to refugees of other nationalities.

Jess Casot recently graduated from the University of Glasgow with a degree in Politics and is pursuing a career in the charitable sector. She works as a freelance journalist, passionate about sharing human stories, and volunteers with UNESCO RIELA and youth football initiatives, committed to building spaces of connection and community.

How the media’s double standard is failing refugees

Every day we consume countless images— photos, graphics and videos that shape our perception of events and the way that we see the world. Social media has made this influence impossible to ignore. Anything can go viral, and anyone can have a platform. When it comes to the stories of refugees, these images can be as misleading and harmful as they can be powerful.

On the 2 September 2015, the world awoke to an image circulating on X (formerly Twitter) of three-year-old Alan Kurdi. He had died attempting to cross the Aegean Sea after fleeing Syria with his family and was found on a beach in Turkey. The image of him on the beach, taken by a Turkish photojournalist in the early hours of the day became internationally recognisable. It is estimated that 20 million people saw the photo in the first twelve hours.

The response was an outpouring of sympathy and outrage. European leaders were called upon to take greater action to support refugees. Within days German Chancellor Angela Merkel dropped the European Union’s (EU) Dublin Regulation, giving refugees the right to claim asylum beyond the first EU country that they step foot in. The huge shift in policy has been directly linked to the outrage caused by Alan Kurdi’s death. The young boy became considered a ‘symbol’ of refugees everywhere.

Why did Alan’s death resonate so profoundly, when in April of that year, 750-900 asylum seekers died when their boat capsized off the coast of Italy, yet it is barely registered in public memory? The answer lies in how these events were presented.

To understand why images provoke strong reactions, researchers have looked at the psychology of visual empathy. Roland Bleiker theorised that images that represent pain or suffering are more likely to invoke an emotional response, especially a single victim, but for every additional person visualised, the effect is diluted. Images can inform our perception of events, and directly impact our response.

Age and gender, according to Nils Christie, are signifiers of increased vulnerability and deepen people’s emotional connection to events. In this context, images that depict a young child crying or a worried looking mother, are more likely to garner attention and sympathy. Mothers and children, Bleiker says, are one of the world’s most recognisable humanitarian symbols; markers of a population in crisis.

The geopolitics of the past ten years has been accompanied by mass-displacement. Civil War in Syria, the Taliban resurgence and takeover of Afghanistan and the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, among many others. The EU’s refugee population increased from 2.1 million in 2010 to 7.4 million in 2023. However it is difficult to understand the true numbers, given the Ukrainian refugees’ special status under EU law.

What quickly emerged from the mass displacement brought about by Russia’s full-scale invasion, was a difference in the narrative presented around their displacement, compared to refugees of other nationalities. Academics have pointed to language, culture and race. German media for example used words like ‘influx’ to describe Ukrainians in Germany, avoiding the term ‘refugee crisis’. There was an emerging bias in the way Ukrainian refugees were being perceived and reported. Bulgarian Prime Minister Rumen Radev in February 2022 was quoted bluntly:

“These people are Europeans. These people are intelligent. They are educated people… This is not the refugee wave we have been used to, people with unclear pasts, who could have been terrorists.”

There was an outpouring of support for Ukrainians across the Western world, deeply entwined with the concept of the ‘ideal victim’, informed by centuries of oppression. Orientalism, whereby European colonists constructed ‘the Orient’ as an entirely foreign land, with people unlike ‘us’ (the white European) has lived on in the form of hierarchies of suffering. The Ukrainian population is considered familiar; largely white, Christian, sharing many cultural traditions with other Western countries.

I decided to test whether these biases extended to representation in the media, comparing how Ukrainian refugees have been visualised and reported, to refugees of other nationalities. To do this, I analysed photographs posted under articles in newspapers of Afghan refugees in the three months following the Taliban takeover on 15 August 2022. I then looked at photographs of Ukrainian refugees following the full-scale Russian invasion on 24 February 2022, within a similar three month period.

Examining their appearance within prominent newspapers in the United States, the Wall Street Journal (politically right-leaning) and the New York Times (politically left-leaning) meant I could remove geographical proximity to Ukraine as a factor influencing reporting. I was more interested in who featured in the photographs and what kind of headlines were accompanying them.

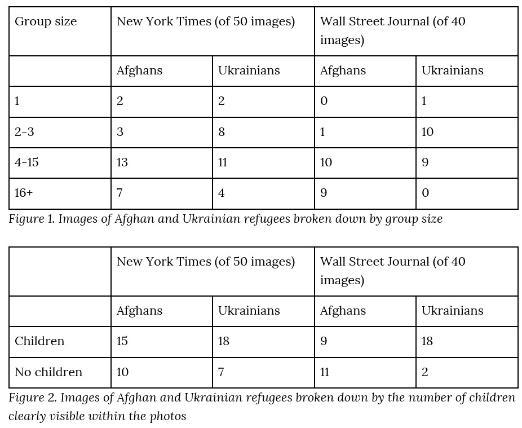

I was able to gather 40 images from the Wall Street Journal (20 of Afghans, 20 of Ukrainians) and 50 from the New York Times (25 of Afghans, 25 of Ukrainians) which had more extensive coverage of refugees. I looked at the size of groups represented in photos, and whether children could be clearly identified in these photos. This was to test both Bleiker and Christie’s statements on what kind of images created an emotional response.

A full document of the photographs and links to articles can be found here.

The results were compiled into two tables. Figure 1 and 2 show a clear contrast in how children and individual victims are represented among Afghan and Ukrainian refugees.

If people are more likely to express sympathy with single victims, and this is diluted with every additional person, visual media could have a significant impact on societal perception of refugees. Children, considered to be the most vulnerable in society in Western culture, were far more likely to feature in photos of Ukrainians.

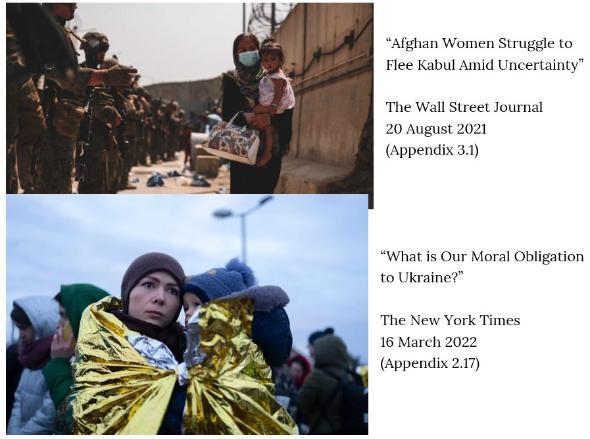

Even when comparing similar images, headlines could influence perception of the issues. Among several photos of mother and child, only one featured an Afghan woman and child. The headline reads: ‘Afghan Women Struggle to Flee Kabul Amid Uncertainty’, surrounded by soldiers, creating its own visual imagery. By comparison, a similar photo of a Ukrainian mother and child reads ‘What is Our Moral Obligation to Ukraine?’, directly implicating the reader to take action.

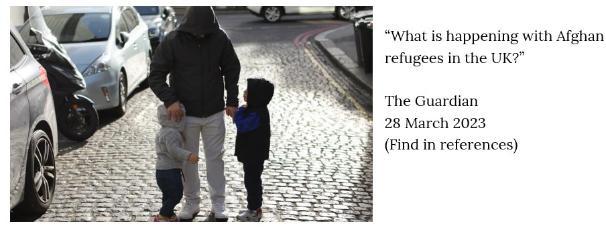

When I conducted a similar comparison of images of Afghans and Ukrainians in British newspapers, I came across similar results. Children were more likely to feature in photos taken of Ukrainians, and they were more likely to be photographed in small groups or as individuals.

Headlines revealed contrasting humanitarian or harmful narratives. One photograph shows a father and two children, all three hooded and silhouetted. Even if this was a privacy choice, the headline adds to the anonymity of the photo; invoking uncertainty rather than an emotional response. This is vastly different to the other photo of a Ukrainian woman crying as she, similarly, embraces two children. The headline highlights the newspaper’s own Ukraine appeal.

Humanitarian frames are more likely to create sympathetic, action-oriented responses to events. It is vital that we scrutinise our media and how they represent refugees as emotionally muted narratives can distort public perception. Every refugee is protected equally under international law, yet our media undermines this by presenting unequal narratives.

Media organisations reinforce hierarchies of suffering— but so do we when we consume their content uncritically. We must question the images we see and the stories we share. If we see beyond the frames placed before us and actively critique them, we work towards a culture of empathy that treats every refugee with dignity, turning fleeting sympathy into meaningful, lasting support.

References

Adler-Nissen, R., Anderson, K. E. & Hansen, L., 2019, ‘Images, emotions, and international politics: the death of Alan Kurdi’, Review of International Studies, 46(1), pp. 75-95. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210519000317 [Accessed 7 February 2025].

Bleiker et al., 2013, ‘The visual dehumanisation of refugees’, Australian Journal of Political Science, 48(4), pp. 398-416. Available at: https://doi-org.ezproxy1.lib.gla.ac.uk/10.1080/10361146.2013.840769 [Accessed 29 January 2025].

Bleiker, R., Campbell, D. & Hutchison, E., 2014, ‘Visual Cultures of Inhospitality’, Symposium: Migrants and Cultures of Hospitality, Peace Review: A Journal of Social Justice 26, pp. 192-200. Available at: https://doi-org.ezproxy2.lib.gla.ac.uk/10.1080/10402659.2014.906884 [Accessed 7 February 2025].

Cohen, D., 2022, ‘Refugees Welcome: Joeley Richardson and Erin O’Connor add support to our Ukraine appeal’, The Independent. [Online]. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/joely-richardson-erin-o-connor-ukraine-b2030023.html [Accessed 11 September 2025].

Krutrök, M. E. & Åkerlund, M., 2023, ‘Through a white lens: Black victimhood, visibility, and whiteness in the Black Lives Matter movement on TikTok’, Information, Communication & Society, 26(10), pp. 1996–2014. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2022.2065211 [Accessed 12 February 2025].

Pinney, R., 2015, ‘The Aylan Kurdi Effect: Can a Single Photograph Really Change History?’, Rob Pinney. Available at: https://www.robpinney.com/blog/aylan-kurdi-response [Accessed 7 February 2025].

Rockwool Foundation, 2025, ‘The Immigrant Population in the European Union’, The Rockwood Foundation. [Online]. Available at: https://www.rfberlin.com/immigrant-population-eu [Accessed 29 August 2025].

Said, E., 2003, Orientalism (New York: Vintage Books).

Schwöbel-Patel, 2018, ‘The ‘Ideal’ Victim of International Criminal Law’, The European Journal of International Law, 29(3), pp. 703-724. Available at: http://ejil.org/pdfs/29/3/2909.pdf [Accessed 10 February 2024].

Syal, R., 2023, ‘What is happening with Afghan refugees in the UK’, The Guardian. [Online]. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/mar/28/what-is-happening-with-afghan-refugees-in-the-uk [Accessed 11 September 2025].

Tjaden, J.& Heidland, T., 2024, ‘Did Merkel’s 2015 decision attract more migration to Germany?’, European Journal of Political Research, 64(1), pp. 389-405. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12669 [Accessed 7 February 2025].

First published: 12 September 2025